In the woods, food is abundant, but I would starve within weeks without grocery stores.

As the deer circle my house, they nibble here and there, chew up the small leafy pecan tree branches that fall to the ground, and eat almost every flower, sparing only a few natives like red buckeye and cutleaf coneflower.

Centuries ago, the Tunica people foraged on this land the way the deer do—with knowledge and confidence. The elders among them both taught the young what was safe to eat. What had purpose for one wasn’t necessarily for the other. The Tunica roasted and boiled yaupon holly leaves—this we know because of Jesuit reports to their colonizing patrons—to make the Black Drink, a caffeinated beverage used in ceremonies. I haven’t seen the deer eat those holly leaves or the red berries that ripen in late winter, although I read they will if there’s nothing else.

The summer when I first noticed hundreds of yellow flowers thriving in the woodland shade—bright sparks among the tiers of green—I had to know what it was. The common name, cutleaf coneflower; botanical, Rudbeckia laciniata; the name the Cherokee call it, sochan. Deer didn’t appear to eat any of the plant, but the Cherokee, and likely the Tunica, use the leaves for food.

Raw, it’s rough and not too bitter. Sauteed with olive oil, there’s a wild depth. As the taste fades, I feel wide awake, my body soaking in pure food that grew in healthy soil.

In the late spring, as the sochan matures, weeks away from blooming, the dark forest floor pops with flares of dark gold. When I first noticed them a couple of years after I moved here, I knew they were mushrooms but nothing like I’d seen in the urban places I once lived. A neighbor who knows her fungus delivered a small bag of them—chanterelles. Very good eats, when you’re sure of what you’ve picked.

This late May, the sunny, frilled caps dotted under this oak, up through that patch of ground, and another, and within days, I could have gathered enough to feed a dinner party. I picked plenty for myself and filled the kitchen with their deep, earthy scent as they cooked. Stuffing my face with what the land offered freely ($30 or more a pound if I bought them), I looked out of the window and thought of my ancestors in Old World forests, grandmothers whose grandmothers showed them what was food, what was medicine, what was both.

From books, apps, and workshops, I can learn what else to forage on this land where I’m a stranger. The knowledge is recorded. It’s not lost.

But I’m missing what the deer have, what the Tunica and my long-dead grandmothers had. At my side, an elder of my blood or community who can teach what should be second nature to feed my belly and soul.

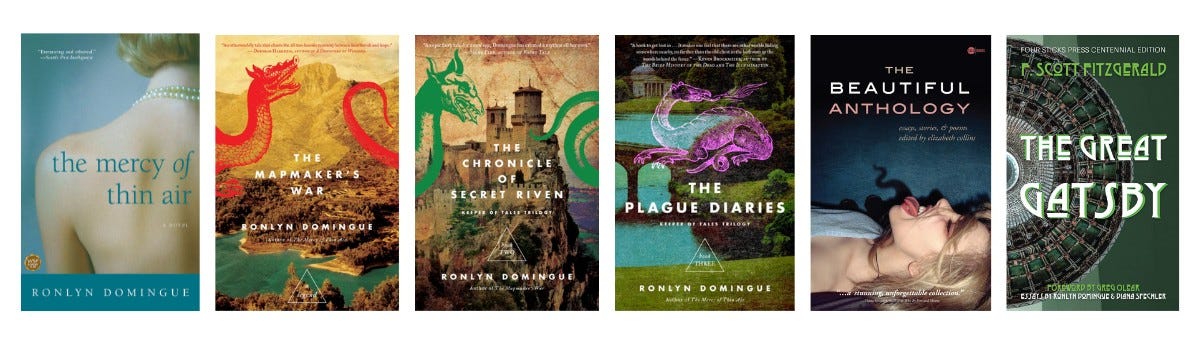

Thank you for reading CRONE ENERGY. I write about deep, sensitive people in strange, transformative circumstances, which obviously includes me. That also refers to my four novels—The Mercy of Thin Air and the Keeper of Tales Trilogy (The Mapmaker’s War, The Chronicle of Secret Riven, and The Plague Diaries).

My essay, “Milkweed and Metamorphosis,” appears in The Beautiful Anthology.

The Great Gatsby is 100 years old this year, now in the public domain. I contributed an essay in the Four Sticks Press Centennial Edition.