Alone for a couple of weeks, here at my woodland home, I stayed busy with DIY projects to keep ruminations at a minimum. Not that I was successful at this.

As depraved incompetents stand poised to take over the US in a few weeks, I pondered—with no firm decisions yet made—about how to deal with the people in my life who have absolutely no problem with what’s coming, who don’t realize they will suffer consequences for their choice in some way. Disruptions, inconveniences, higher costs, maybe even death, but I guess they’ll think it’s worth it in the big picture.

For a few days, I couldn’t get the Anne Frank quote out of my head: “In spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart.” She was a teenager when she wrote those words. Such hope was hers to hold as she hid in the Secret Annex. I was about her age when I first read her diary, the excised version, and I cupped that shimmery belief as well. With so little life experience and too much idealism, how could I not?

I don’t know how to navigate the coming years and interactions. At different times, depending on the situation, I’ve walked the high road (a friend often remarked where there’s less traffic); or stepped right up to stand for something or someone I believed in; or strived to keep peace. The latter, oh, that’s a hard one, because it’s not just about my nature to want people to get along—it’s fraught with my Southernness, my whiteness, my womanness, my general conflict aversiveness.

While I puzzle about the future, I mull over the past. Me thinking I am good at heart, the high road is the place to be, peace is meant to be kept. The decision I made to shake the hand of the former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan when I was in my early 20s; the perspective I had in my 40s.

The essay below originally appeared on The Weeklings, a literary essay site founded by

. While I don’t fault my younger self for her decision, I challenge my early middle-aged writer self’s attempt to justify it. Now into my crone years, I realize I’ll always question the choice I made, and the fact I still think about this reveals the stain that proximate evil left behind.********

As the polished brass elevator doors closed, she pressed her back against the side wall. She was traditionally pretty, this legislative page, as most of the young female pages were. Her navy blue blazer fit well, although it bunched as she drew in her shoulders. She was probably a sorority girl or a political science major, or both.

I nodded in silent greeting. Perhaps she assessed me, too, with my hippie-long hair tied in a ponytail, no make-up, T-shirt, and jeans. Just another random student worker. An English major, she might have thought, or something in the hard sciences.

We were alone on a long ride along the 34 floors of the state capitol building.

She glanced at me, her eyes troubled, her expression grim. “David Duke wants me to go to his office,” she said.

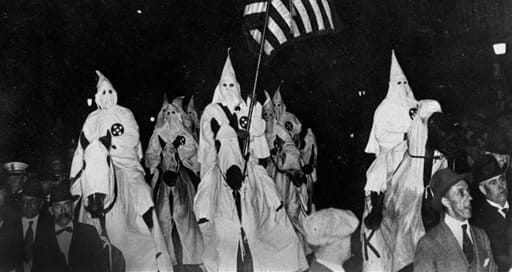

For those who aren’t familiar with that name, or whose recollections are vague, David Duke became nationally famous after running for Louisiana’s governor in 1991. He had a documented past of carrying books and posters bearing Nazi swastikas while a student at Louisiana State University, served as the Grand Wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and was the founding president of the National Association for the Advancement of White People.

At the time the page and I stood in the elevator, Duke was a member of the Louisiana House of Representatives. His background and resume were no secret to his constituents in Metairie—a predominantly white suburb of New Orleans. It would be easy to cast these voters as racist. But Duke’s appeal had been gauged during his unsuccessful run for a U.S. Senate seat in 1988. Polls noted that frustration with the political system influenced people’s votes in greater numbers than agreement with what Duke claimed he no longer believed.*

Call me cynical, but I didn’t think Duke had disavowed his past. His use of the term “welfare underclass” seemed to have a not-so-hooded connotation, and he was a sponsor of legislation to weaken the state’s affirmative action statues. My opposing viewpoint on issues of race wasn’t the only reason I had no fondness for Duke. By then, I was a grassroots activist for women’s reproductive rights (if only I had a nickel for every time I’d been called babykiller, whore, or jezebel), and Duke was firmly anti-abortion. In 1990, he cast one of the 141 votes, out of 144, for a bill that would have mandated 10 years of hard labor to those convicted of performing an abortion, even if the woman was a victim of incest or rape.

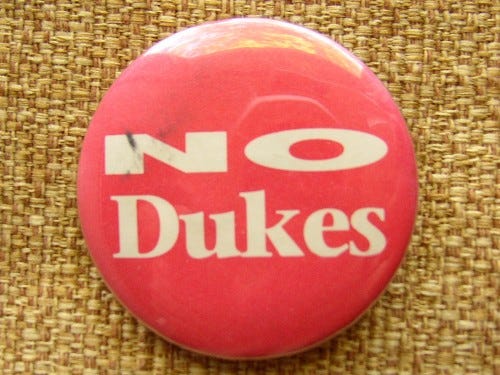

For these, and many other reasons, I had a No Dukes button pinned on my knapsack. He was not getting my vote for governor. What he stood for, even the thought of him, repulsed me.

The page cast her eyes to the elevator floor. She didn’t know me, but she somehow knew that I knew what kind of reputation Duke had in the Capitol, as did several other legislators. It wasn’t unusual for pretty young girls to be invited to their offices, in private. There was plenty of titillation even if there was never any touching.

A hot flare of anger burned to the surface of my skin. I felt the urge to shield her somehow. “Listen,” I said quietly, seething inside. “You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to do. You don’t. Think very carefully before you decide.”

She nodded without a hint of a smile. The elevator opened, and she stepped out. I never saw her again, so I never learned what she decided to do.

I was infuriated on her behalf. In my youthful smugness, I pondered how I’d assertively handle a similar situation, how I’d stand up for myself and what I felt was the right thing to do. No way, I thought. No way could I tolerate even going near someone like that.

Then I got my chance.

In March 1991, I attended a conference held by the Louisiana Press Women’s Association. I’d applied for their one annual scholarship for female journalism students and would receive my award at the luncheon. That morning, in a conversation with one of the committee members, I was told the reason why I received the scholarship. What distinguished me were not my grades or my writing but the feminist activism I’d taken the risk to list. I had never been rewarded for my rabblerousing before. This was also a clue about the crowd that would greet the men speaking at one of the day’s big events—a forum with the gubernatorial candidates.

Incumbent Gov. Buddy Roemer was noticeably absent—skipping many such public events was his M.O.—but his opponents showed up. Of the four men there, the two of greatest interest were David Duke and former governor Edwin Edwards, the rascally lothario who, many agreed, tried to do right for the citizens as well as himself. By then, Edwards had been indicted by the federal government but not convicted (yet). As a nod to Edwards’ notoriety and fears of Duke’s viability, some voters would plaster their cars with bumper stickers which read, “VOTE FOR THE CROOK: IT’S IMPORTANT.”

Before the forum was scheduled to start, I sat down next to a new acquaintance from another university, the two of us chatting away amiably about our common interests, including journalism and women’s rights. It didn’t occur to me that the candidates would do anything except sit on the dais and share their usual sound bites—grumbles about taxes, affirmations about the importance of education, assertions that they were solidly pro-life.

But then, the conference doors opened and the candidates walked into the room. They approached the women who were already seated in rows, extending their hands.

“Oh no,” my acquaintance said. “There’s David Duke.”

I whipped my head to the right. There he was, his sculpted face (he’d had plastic surgery in 1988) smiling as he inched into the room.

We whispered our dismay. What would we do? Leave? Stay? Refuse to shake his hand?

My mind twirled under my hippie-long hair. What this man stood for was repugnant to me, which meant he was. Would it be a political action to keep my hands at my side? Was that the right thing to do? And then an unbidden insidiousness leached under my skin. As David Duke came ever closer, I tried to fight my upbringing—to respect my elders—and my indoctrination as a woman, especially a woman from the South—to be polite and accommodating.

My heart writhed in my chest. Could I live with myself if I did this, or if I didn’t?

“Hello,” David Duke said, his hand out.

My acquaintance accepted the gesture in silence.

He turned to me. I shook his offered hand. I noted the practiced political smile, and I met his eyes. They were not cold or cruel. His suit was traditional, appropriate, even tasteful. My flesh didn’t crawl, nor did my gag reflex kick in. If I hadn’t known who he was, I might have guessed he was an accountant, someone quite mild. He was so…ordinary. Then with a pivot, he moved to the next person.

So that’s what a minion of evil looked like.

That November, I voted for the crook, who won by 61 percent. For years afterward, however, I was plagued by the handshake, as if I’d done something wrong. But I hadn’t. On the opposite side of that handshake was Duke’s nemesis, a progressive young woman who viewed the world with different definitions of freedom, rights, and liberty. I was his other. Rejection works both ways. These days, I like to think there’s a shred of hope for our divided country and strife-ridden world as long as adversaries can stand face to face in a simple greeting. I saw for myself that the other side is human, too.

* Maginnis, John. Cross to Bear: American’s Most Dangerous Politics. Baton Rouge, LA: Darkhorse Press, 1992. p. 88